Prescott, J., Soo, J., Campbell, H., & Roberts, C. (2004). Physiology & behavior, 82(2-3), 459-469.

Masi, C., Dinnella, C., Monteleone, E., & Prescott, J. (2015). Physiology & behavior, 138, 219-226.

Monteleone, E., Spinelli, S., Dinnella, C., Endrizzi, I., Laureati, M., Pagliarini, E., Tesini, F. (2017). Food Quality and Preference, 59, 123-140.

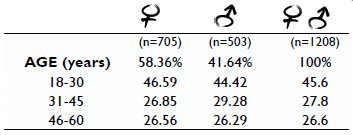

The approach followed in this study is promoted by the project PLOTINA-Promoting gender balance and inclusion in research, innovation and training (www.plotina.eu) to include the variable sex/gender in the founding objectives of the research. The abovementioned classification among males and females was performed according to participants self-declaration and GENDER is “a socio-cultural process that refers to cultural and social attitudes that together shape and sanction “feminine” and “masculine” behaviors, products, technologies, environments, and knowledges. of gender identities. “Gender does not necessarily match sex.” (Gendered Innovation Lexicon). This study was supported by PRIN 2015 and followed the procedures of the Italian Taste project.